AI-powered delivery date estimates to boost conversion

Give shoppers peace of mind and protect and grow your bottom line

Personalized tracking experiences to build brand loyalty

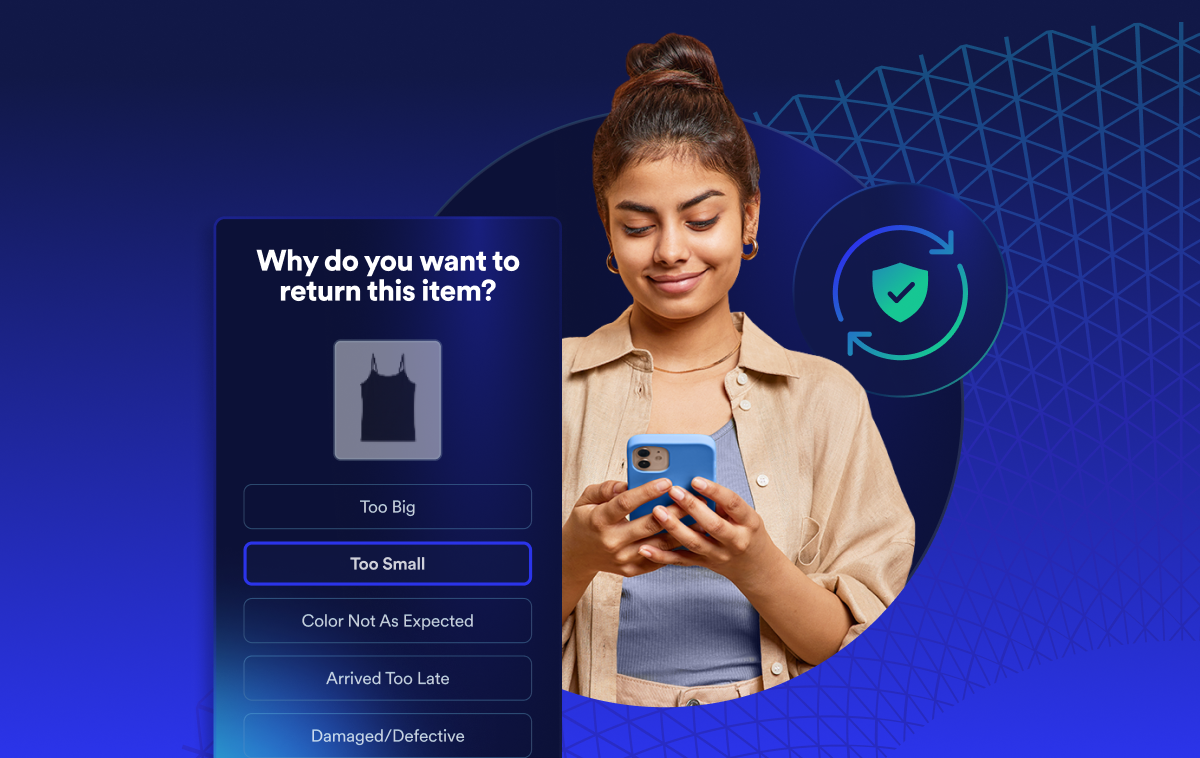

Returns and exchanges management to mitigate fraud and reward best customers

Proactive communication to drive customer lifetime value

Delivery claim management to tackle fraud and build trust

Cost of Goods Sold (COGS): Definition, Formula, and Examples

%20(31).webp)

Looking at a company’s total revenue tells an incomplete story about its financial performance. While earning millions—even billions—of dollars in gross revenue may make for a splashy news headline, true financial success comes from how much of that revenue a company manages to retain, after all costs are taken into consideration. Cost of goods sold (COGS), for example, is one data point that factors into understanding a company’s holistic financial picture.

Here, we’ll take a deep dive into what COGS is and how it’s calculated, using real-world ecommerce examples.

What’s the definition of cost of goods sold (COGS)?

Cost of goods sold represents the total cost to produce a product. A simple example makes the cost of goods sold definition clearer: If it costs your ecommerce company $5 to make a coffee mug, your COGS is $5 no matter how much you sell it for.

Generally speaking, COGS encompasses any direct costs associated with producing an item. In the cost of goods sold example above, this might include the costs of:

- The clay, if you’re making the mug by hand

- Pre-made mugs you import, as well as any materials used to decorate or otherwise transform the mugs

- The labor costs associated with making the mugs or preparing them for sale

- Freight costs to get pre-made mugs to your warehouse, as well as any duties or fees incurred

Conversely, COGS does not include overhead expenses or indirect labor costs. In this case, warehouse rental fees or utilities for the space where you store your mugs aren’t considered to be a part of COGS, nor are any sales or marketing expenses you incur to sell your items. Freight costs or shipping costs to get your mugs out of your warehouse and to your customers are similarly excluded.

Cost of goods sold is typically reported on your business’s income statement within a special COGS account. Getting this number right is important, as reporting COGS is a tax requirement. If you want to be able to write off the cost of your goods at tax time, you’ll need to provide the IRS with an accurate accounting of your eligible expenses.

Beyond reporting requirements, COGS drives gross margin calculations. Without a full and accurate understanding of the cost of its goods, companies risk overestimating their profitability. This can lead to unsound business decision-making that leaves companies in a financially-risky position.

What’s a cost of goods sold formula?

How to calculate cost of goods sold might seem like a simple question, but there are actually several COGS formula variations that take the complexity of modern business into account.

Consider our coffee mug example. While it’s easy to identify the cost of producing a single mug, what happens to your calculation if you hold thousands of mugs in your inventory? How do you calculate COGS if you’ve purchased some of these mugs at different prices, if your labor costs have varied over time, or if the shipping fees you’ve incurred have changed from delivery to delivery?

With these challenges in mind, here are a few of the different cost of goods sold formulas you may encounter.

Specific Identification

The specific identification model is the closest to our coffee mug example, as in this case, you track COGS on an item-by-item basis. If you had 10 mugs in your inventory, for example, you’d track the costs associated with each mug, taking into consideration any variability in materials costs, labor hours, or other expenses.

Given the labor requirements associated with this method, it’s more commonly used for high-dollar, customizable items, such as custom gaming laptops or high-end antiques.

Weighted Averages

Calculating COGS according to weighted averages lets you track approximate costs across a larger group of items. For example, imagine that, in your inventory, you had:

- 100 coffee mugs at a COGS of $5

- 100 coffee mugs at a COGS of $6

- 100 coffee mugs at a COGS of $7

Rather than accounting for each mug’s cost individually, you’d total both the number of items and their COGS, then divide the total COGS by the total number of inventory items. Here’s what that looks like in practice:

Total COGS: 100 x $5 + 100 x $6 + 100 x $7 = $1,800

Total Inventory: 100 + 100 + 100 = 300 mugs

Weighted Average: $1,800 / 300 mugs = $6 COGS per mug

Because the weighted averages method treats inventory as a pool, it’s best suited to retailers that sell high-volume goods around a similar price point.

‘First-In, First-Out’ (FIFO)

Like the weighted averages model, FIFO also treats inventory as a pool. However, it differs in that it assesses COGS based on the order in which items were purchased and sold.

Here, imagine that the 300 mugs from our previous example were purchased in the following months:

- 100 coffee mugs at a COGS of $5, purchased in April

- 100 coffee mugs at a COGS of $6, purchased in May

- 100 coffee mugs at a COGS of $7, purchased in June

If, in July, the retailer sells 150 mugs, the FIFO COGS calculation would assume that 100 of the mugs purchased in April and 50 of the mugs purchased in May (the ‘first in’ inventory) were sold—regardless of which mugs were actually shipped. As a result, the total COGS associated with mugs sold in July would be calculated as:

Total COGS: 100 x $5 + 50 x $6 = $800

‘Last-In, First-Out’ (LIFO)

Opposite to the FIFO model, LIFO assumes that the most recently purchased inventory is sold first. Repeating our calculation above, the COGS associated with the 150 mugs sold in July becomes:

Total COGS: $100 x $7 + 50 x $6 = $1,000

Choosing the right COGS model

While it may seem strange that costs of goods sold calculations could produce different outcomes, each of the four methods above are accepted under U.S. Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP). Choosing the right model for your business depends on a number of factors, including, among others:

- Current market conditions: If prices in your market are rising, the LILO model may better approximate your current costs.

- Tax strategy and financial reporting: Higher COGS results in higher deductions, which may be either desirable or undesirable according to your tax strategy or the story you want your financial reporting to tell.

- Your ecommerce tech stack: More complex COGS calculations require more advanced technology to remain accurate. For example, data from your inventory system or returns solution need to be incorporated into your accounting workflows to ensure accurate COGS reporting.

Regardless of the model you choose, regularly reviewing your reported COGS ensures an accurate financial picture and may help prevent fraud. Pay attention to this important number in order to make smart decisions on everything from purchase planning to pricing policies.

If you liked this article, you may also like, “How to Calculate Inventory Turnover,” or "What is an RMA: Meaning, Use Cases, and Best Practices."

Get more insights from the experts

GET STARTED

Power every moment after the buy

Build trust. Protect margins. Drive growth — “Beyond Buy.”